The Transition Gap: Navigating the Structural Misalignment of the Valley of Death

- Jordan Clayton

- Jul 9, 2025

- 4 min read

A technology firm achieves what feels like a definitive victory. They secure a $1.5 million SBIR Phase IIaward and a prototype Other Transaction Authority (OTA) contract from the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU). Over the next 18 months, the team executes flawlessly, delivering a validated capability that end-users enthusiastically support. The product works. The warfighter wants it. The investors are ready to scale.

Then, the funding ceases. The emails to the Program Office go unanswered. The firm’s burn rate consumes its remaining capital. The technology, despite its brilliance, dies on the shelf.

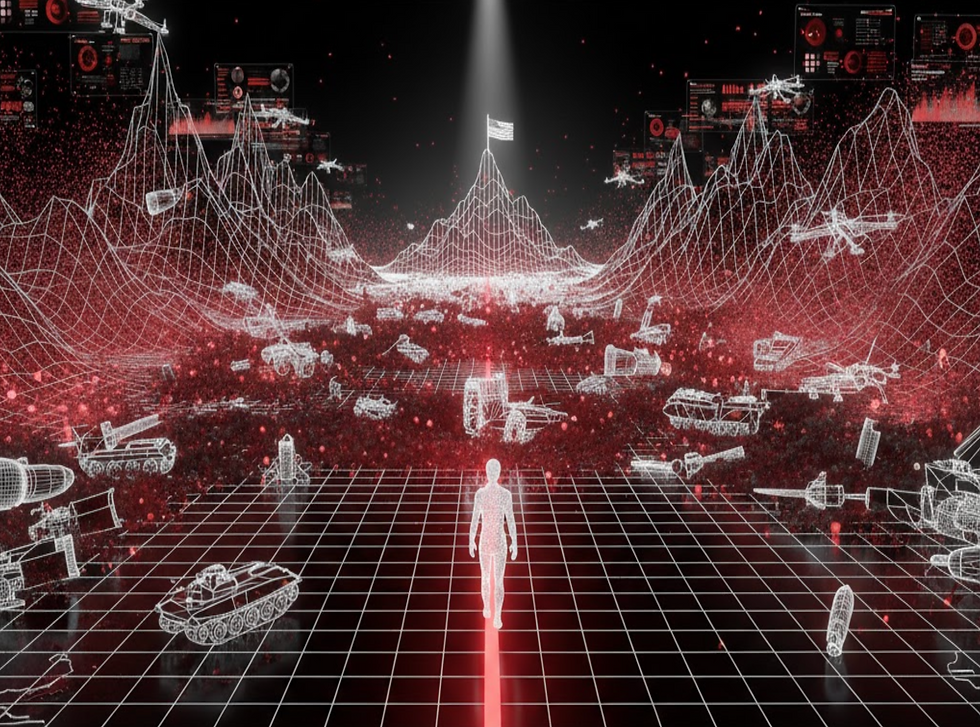

The firm has entered the Valley of Death.

This phase is the most lethal transition in the defense acquisition lifecycle. It is frequently misdiagnosed by founders and venture capitalists as a "sales problem" or a "marketing failure." In reality, it is a structural misalignment between two distinct legal and financial systems . The firm has been operating on "fast" RDT&E (Research, Development, Test & Evaluation) dollars designed for experimentation. To scale, it must transition to "slow" Procurement dollars designed for sustainment.

The Valley is not a myth; it is the temporal chasm where RDT&E expires before Procurement is appropriated. Survival requires a fundamental shift in corporate posture from "technology development" to "programmatic transition." You are no longer building a product; you are building a budget line item.

The Anatomy of the Chasm: Two Worlds, One Department

The Valley exists because the Department of Defense (DoD) is not a single customer; it is a federation of disconnected checkbooks with different authorities and timelines .

1. The Innovation Pipeline (The Incubator) Organizations like DIU, AFWERX, and Army Futures Command utilize RDT&E funds (typically "2-year money").

The Dynamic: These contracts are short-term (12-24 months), flexible, and designed to prove feasibility.

The Limit: These organizations are incubators, not adopters. They can fund a prototype, but they legally cannot buy a fleet. They do not own the long-term sustainment budget .

2. The Program of Record (The Adopter) Major Program Executive Offices (PEOs) utilize Procurement ("3-year money") and Operations & Maintenance (O&M) ("1-year money") funds.

The Dynamic: These budgets are planned 24-to-36 months in advance via the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) cycle. They are rigid, regulated, and massive.

The Limit: A PEO cannot spend money they did not ask for two years ago. If your technology wasn't in their budget request in FY23, they likely cannot buy it in FY25 without difficult reprogramming actions.

The Structural Failure: If a firm arrives at the end of a prototype contract without a transition partner who has alreadyprogrammed the Procurement dollars to "catch" them, there is no legal mechanism to continue the work. The technology becomes an orphan—validated but unfunded.

The Drivers of Attrition

Firms do not fail in the Valley because their technology is flawed; they fail because they encounter structural barriers for which they are unprepared.

1. The Sponsorship Void: A common failure mode involves optimizing technology for the incubator rather than the ultimate acquirer.

The Trap: Focusing entirely on satisfying the AFWERX technical point of contact or the end-user on the ground.

The Reality: AFWERX does not own the long-term requirement. Without a dedicated transition sponsor within a PEO who has written the capability into their Program Objective Memorandum (POM), the technology has no home. The incubator is the investor; the PEO is the customer.

2. The Compliance Cliff: Prototypes often enjoy relaxed compliance standards to encourage speed. Programs of Record do not.

The Trap: Assuming compliance can be handled "after we win the production contract."

The Reality: Transitioning to production triggers the full weight of federal regulation. This includes CMMC Level 2 cybersecurity certification, DCAA-compliant cost accounting, and strict supply chain vetting (Section 889). Firms that are not audit-ready at the moment of transition are disqualified as "high risk," regardless of technical merit.

3. The Integration Wall: Startups often build standalone solutions. The DoD buys integrated systems.

The Trap: Proving your algorithm works in a vacuum but failing to prove it works inside the legacy architecture controlled by a Prime contractor.

The Reality: If the Prime resists integration and the Program Office lacks the technical data package to force it, the pilot enters "purgatory" and dies .

Strategic Counter-Measures: The Transition Playbook

To cross the Valley, firms must stop acting like R&D labs and start acting like defense contractors. This requires a "Transition-First" methodology.

1. Identify the Acquirer at Inception (Day Zero) Do not accept R&D funding without a hypothesis of who will buy the production unit.

The Action: Map the PEO landscape. Identify the specific Program Element (PE) line that funds the legacy capability you intend to replace or augment. Engage the Program Manager (PM) early and get their written endorsement as a prerequisite for transition funding . If you cannot find the money in the budget, it does not exist.

2. Synchronize with the PPBE Cycle Transition planning must begin 24 months prior to the end of the prototype phase.

The Action: While building the prototype, you must arm your future champion with the artifacts required to program the budget for the out-years. Provide the Rough Order of Magnitude (ROM) cost estimates, the Capabilities Description Document (CDD) inputs, and the transition schedule. You are essentially ghostwriting the budget request that will pay you in three years.

3. Weaponize Compliance Establish DCAA and CMMC readiness during the prototype phase.

The Action: Use the overhead from your SBIR/OTA contracts to fund the implementation of compliant systems. This removes "transition friction" and signals to the acquiring PEO that you are a mature, low-risk partner capable of handling a major contract.

4. The Bridge Fund Strategy Recognize that a gap is likely inevitable due to budget cycle lag.

The Action: Aggressively pursue bridge mechanisms such as SBIR Phase II Enhancements (TACFI/STRATFI)or follow-on OTAs designed to extend the runway while waiting for the procurement budget to unlock .

From Prototype to Program

The Valley of Death is a structural reality, but it is navigable with precise planning. It requires moving beyond technical demonstration to programmatic integration. The goal is not just to build a widget that works; it is to build a program that survives the budget cycle.

The Valley of Death is where good tech goes to die because bad strategy led it there. At DualSight, we provide the Strategic Advisory to identify transition partners early and the Operational Rigor to ensure your firm is compliant, funded, and ready for the Program of Record. We build the bridge while you build the tech.